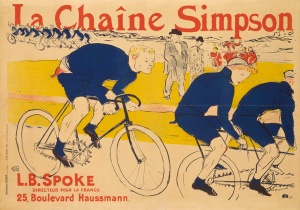

On 6 June 1896, Jimmy ‘The Mighty Midget’ Michael, the reigning World Champion at 100 km participated in a series of races called the ‘Simpson Lever Chain Challenge’, which were cooked up by William Spears Simpson to demonstrate the superiority of his peculiar new bicycle chain. Although the chain was pure snake-oil and quickly disappeared from the scene, the races, which came to be known as the ‘Chain Races’ and were held at the Catford Cycling Club Track in London are central to the story of his manager Choppy Warburton, Michael and Warburton’s other charges, and Warburton’s lasting legacy in cycling, which largely flowed from his little black bottle and its mysterious contents.

Before gaining fame as a trainer of World Champion cyclists, Choppy looked destined for a life in the cotton mills of Lancashire where he grew up. Like most youths growing up in poor, working class families in Lancashire in the 1850s and 60s, Choppy began working down at the mill at a young age (presumably for tuppence a month like his neighbors in Yorkshire). However, Choppy’s athletic and entrepreneurial gifts provided him with a route that would take him far from the mills of Lancashire, even if not quite all the way to the decadent luxury of the four Yorkshiremen:

Choppy’s work at the mill involved meeting trains at the switch and then following them along the spur to the mill, and instead of walking back, he would run back alongside the train. The mill-owner, a sportsman in his own right, noticed Choppy running, and realized he had the making of a runner on his hands and encouraged Choppy to race. Spurred in part by workers having new leisure time and more pay as a result of the Trade Union Act of 1871, sporting activities were then developing into a professional enterprise instead of just a diversion for gentlemen of means. With his talent and the changing times, running turned out to be Choppy’s way out of the mill although it would not provide an immediate exit. Choppy began by competing on Sundays and holidays, fitting it around his mill-work, but eventually he became successful enough as a runner (or pedestrian as they were known at the time) to travel to the United States for a series of races.

However, not dying young, Warburton was confronted with the problem all athletes face as they get older, which is what to do next. Warburton took what would become a well-trodden path for athletes, although he was something of a pioneer, and become a coach once he could no longer run himself. Although coaches were still looked upon with suspicion, as they were believed to subvert the amateur ideal, Warburton believed in the importance of regulated training and that his experience training himself would allow him to make money training other athletes. Warburton began by training runners, but soon realized that there was more money to be made in the burgeoning field of bicycle racing, and despite not knowing how to ride a bicycle, he believed that his general methods would be transferable.

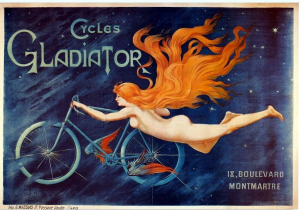

In fact, Warburton proved correct, and his combination of persuasion with regards to talent, showmanship with respect to putting on races, and training proved to be a promising one, and he quickly built up a quality team of racers racing for Gladiator Cycles. One of his strengths was building up a large stable of well-organized pacers, who would ride bicycles built for two, three, four, or even five, and were vital to success in the races of the day. The pacers needed to be trained well-enough to set a high pace and to switch out smoothly so the racer would not lose time or energy changing from one pacing team to another. Despite these successes as a trainer, he is not best remembered for his workouts or the champions he trained, but rather for his mid-race fueling choices that brought him infamy and serve as the crux of the The Little Black Bottle by Gerry Moore. The eponymous bottle, from which his riders would get a potent pick-me-up during the race. When his racers appeared to be hitting a wall in the epic contests of the age, Choppy would appear, bottle in hand and give them a swig, and they would perk up immediately. Given the subsequent history of cycling, this activity has been cited as the first case of doping, however, as the book lays out, there are numerous problems with seeing it that way.

In fact, Warburton proved correct, and his combination of persuasion with regards to talent, showmanship with respect to putting on races, and training proved to be a promising one, and he quickly built up a quality team of racers racing for Gladiator Cycles. One of his strengths was building up a large stable of well-organized pacers, who would ride bicycles built for two, three, four, or even five, and were vital to success in the races of the day. The pacers needed to be trained well-enough to set a high pace and to switch out smoothly so the racer would not lose time or energy changing from one pacing team to another. Despite these successes as a trainer, he is not best remembered for his workouts or the champions he trained, but rather for his mid-race fueling choices that brought him infamy and serve as the crux of the The Little Black Bottle by Gerry Moore. The eponymous bottle, from which his riders would get a potent pick-me-up during the race. When his racers appeared to be hitting a wall in the epic contests of the age, Choppy would appear, bottle in hand and give them a swig, and they would perk up immediately. Given the subsequent history of cycling, this activity has been cited as the first case of doping, however, as the book lays out, there are numerous problems with seeing it that way.

First, no one knows what was in the bottle. Choppy was both a showman who liked to entertain the audience, and if they thought he had a magic potion all the better, and a coach, who felt the same way about opponents, if they thought his riders were unbeatable once they had a drag from the little black bottle, that was all to the good. Second, there were no rules against doping at the time. Cocaine and other useful substances were as close as the nearest druggists and were used by people in everyday life, as can be seen from Sherlock Holmes and his seven-percent-solution. Riders and their coaches, then, were on their own for choosing what would best help training and racing. Third, the cases that are supposed to be examples of his riders becoming ill and/or dying from Choppy’s ministrations are a lot more ambiguous than given out when cited as the first casualties of doping.

Most notably among the controversies involving Choppy’s little black bottle was the one involving Jimmy Michael at the aforementioned Chain Races. Here after a sip from the bottle Michael did not improve his performance, but rather weakened and lost his race badly. He would later accuse Choppy not of giving him performance enhancing drugs, but rather of poisoning him. Although Choppy was sanctioned by British cycling authorities for his actions, Moore suggests that Michael was really making the accusation to get out his contract to allow him to move to a new manager where he would get a larger share of the winnings. Choppy and the Might Midget would both soon pass away, with Michael’s death adding more fuel to the fire of condemnation for Choppy.

The two main weaknesses of the book are that it lacks citations, including for information that seems to be verging into the realm of speculation, especially about the state of mind of Warburton at various times, and that it covers much of the ground in the book multiple times. Many races, for example, are covered from Warburton’s perspective as well as that of his main riders. Neither of these may be the fault of the author, since he died before the book was published, but they do detract from the impact of the book. Although The Little Black Bottle provides a good aperitif, another treatment of Choppy may be on the way, as Andrew Ritchie, who has written a number of cycling books, including a biography of Major Taylor and who helped to put The Little Black Bottle together after Moore’s death, says that he is working on his own book about Choppy which will be better sourced and more thorough by better engaging with French language sources.

Despite its shortcomings the book provides a fascinating glimpse into the world of early bicycle racing, with the beginnings of the legendary Paris Roubaix and of the World Championships. In the end, whatever the contents of his bottle, Choppy Warburton surely left his mark on the cycling world and set a standard for showmanship and rigorous training for others to build upon.